Widespread government corruption, political influence on the judiciary, attacks on journalists and restricted freedom of assembly are the main problems Bosnia and Herzegovina has regarding human rights violations, according to the US State Department Human Rights Practices report for 2018.

The US State Department also listed harsh prison conditions, restrictions of freedom of expression and attacks against minorities, including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) persons.”

While the constitutions of both the state and those of the two semi-autonomous entities do provide for a fair trial and an independent judiciary, “political parties and organized crime figures sometimes influenced the judiciary at both the state and entity levels in politically sensitive cases, especially those related to corruption,” the report said, adding that “authorities at times failed to enforce court decisions.”

The law also provides for freedom of expression, which also refers to the press, but according to the report, “governmental respect for this right remained poor during the year.”

“Intimidation, harassment, and threats against journalists and media outlets increased in the period leading up to the October general elections, while the majority of media coverage was dominated by nationalist rhetoric and ethnic and political bias, often encouraging intolerance and sometimes hatred.The absence of transparency in media ownership remained a problem,” it said.

The report also mentioned “a number of physical attacks against journalists” in 2018 and cited data by the BiH Journalists Association, which said that authorities prosecuted only about 30 percent of the reported crimes committed against journalists and investigated more than a third of all such alleged cases between 2006 and 2018.

“The trend of politicians and other leaders accusing the media of treason in response to criticism intensified,” it said, exemplifying this with Bosnian Serb leader and Chairman of the tripartite Presidency Milorad Dodik, who in June “accused pro-opposition BNTV journalists Suzana Radjen Todoric and Zeljko Raljic of working against the RS.”

“Using the fact that they went to London to attend a media course and linking this to his earlier conspiracy theory about British spies planning a coup in the RS, Dodik asserted that the journalists received special training in the UK, adding that it was understood what purpose this “training” would serve,” it said.

While it said that the government mostly respected the right to freedom of peaceful assembly, it did name violations, most of all in Republika Srpska.

“In December, however, the RS Ministry of Interior banned a group of citizens from holding peaceful protests in Banja Luka,” referring to the “Justice for David” movement which has been seeking justice in the unresolved murder of 21-year-old David Dragicevic.

The report mentioned the events of December 25, when RS authorities arrested 20 supporters of the Justice for David group, including two opposition politicians.

“Some journalists and protesters have alleged that during the arrests police used excessive force on protesters, and have produced photographs that appear to support their claims,” the report said.

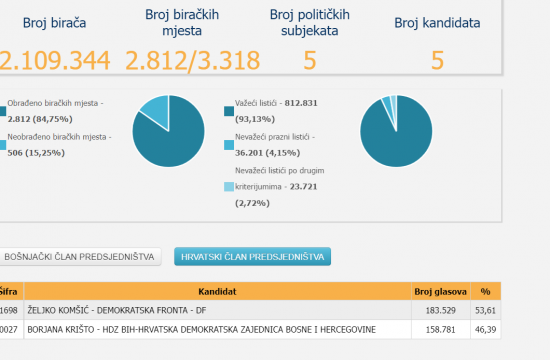

As for the October 2018 General Election, the report said there were “credible reports of voter intimidation and vote buying in the pre-election period.”

International observers reported numerous incidents of political parties “manipulating the makeup of the polling station committees, which endangered the integrity of the election process,” it said.

There were also reports on other irregularities in the ballot counting process, “some deliberate and some due to inadequate knowledge of appropriate procedures among polling station committee members.”

Citing the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, the report said “the campaign finance regulatory system was not adequate to assure the transparency and accountability of campaign finances” and that “several political parties requested recounts.”

While the law does foresee punishment for corrupt officials, “the government did not implement the law effectively nor prioritize public corruption as a serious problem,” it said.

“Officials frequently engaged in corrupt practices with impunity, and corruption remained prevalent in many political and economic institutions. Corruption was especially prevalent in the health and education sectors, public procurement processes, local governance, and in public administration employment procedures.”

However, the report also said that, while the public does recognise corruption as a problem in the country, “there was little public demand for the prosecution of corrupt officials.”

The way in which the state is organised provides for many opportunities for corruption, it said.

“The multitude of state, entity, cantonal, and municipal administrations, each with the power to establish laws and regulations affecting business, created a system that lacked transparency and provided opportunities for corruption. The multilevel government structure gave corrupt officials multiple opportunities to demand “service fees,” especially in the local government institutions.”

Apart from this, it said that state-level institutions, such as the Agency for Prevention and Fight against Corruption, “had limited authority and remained under-resourced,” while the prosecution has been “generally ineffective and subject to political manipulation, often resulting in suspended sentences or prison sentences below mandatory minimum sentences.”

The report mentioned figures by state authorities saying that 84 indictments were submitted targeting high-ranking officials throughout the past five years, yet only 38 of them were found guilty.

Public procurement abuses “generally were not investigated,” the report said.

It pointed out that the process of gathering evidence to prove cases of corruption “has been seriously impeded” when the Constitutional Court declared some provisions of the law governing special investigative measures unconstitutional in 2017, and although the provisions are still in force, no new legislation has been adopted.

“Judicial officials are reluctant to apply these measures until new legislation is adopted for fear judicial decisions will later be appealed,” it said.